Women’s Rights: Who was left out?

March 22, 2021

America’s history of women’s rights consists of trailblazers fighting for women’s fundamental rights and equality, from Abigail Adams imploring her husband, John Adams, to “remember the ladies,” to Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton fighting for women’s right to vote. In America’s early history, women were denied some of the basic rights that men were able to enjoy. Married women couldn’t own property or have any legal claim to money they might’ve earned, and no female had the right to vote. Women were expected to take care of the house and the children and not to worry themselves about politics.

In the decades before the Civil War, starting in the 1820s, various reform groups emerged in the U.S., including the abolitionist movement and religious groups. Although the campaign for women’s suffrage was small, it was beginning to attract attention as women played a prominent role in these movements. American women were resisting the idea that they were just pious, submissive wives and mothers concerned with only their homes and their families. There was a new way of thinking about what it meant to be a woman and a citizen in the U.S.

On July 19th and 20th, 1848, the first women’s rights convention organized by women took place. The Seneca Falls Convention, held in New York, had 300 attendees, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. 68 women and 32 men, including Frederick Douglass, a former African American slave, and activist, signed the Declaration of Sentiments, which sparked decades of activism and eventually led to the passage of the 19th Amendment. Most delegates agreed that American women were autonomous individuals who deserved their own political identities. Following the convention, the demand for the right to vote became the centerpiece of the women’s rights movement.

However, it still took some time and effort before all American women had the right to vote. On May 21, 1919, U.S. Representative James R. Mann, a Republican from Illinois and the chairman of the Suffrage Committee, proposed to the House a resolution to approve the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote. The measure passed in the House 304 to 89—42 votes above the required ⅔ majority. Two weeks later, on June 4, 1919, the U.S. Senate passed the amendment 56 to 25, just two votes above the necessary ⅔ majority. It was then sent to the states for ratification. By March 1920, 35 states had approved of the 19th Amendment, just shy of the ¾ majority required for ratification. Southern states opposed the amendment, including Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia. On August 18, 1920, it came down to Tennessee’s vote, which resulted in a 48 to 48 tie. Republican Harry T. Burn, the tiebreaker, was opposed to the amendment, but his mother convinced him to approve it. On August 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment was certified by U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, granting women the right to vote.

The 19th Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” While passage of the 19th Amendment enabled most white women to vote, people with marginalized identities were often excluded from the right to vote. After the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, women of color were often kept from polls. African American women faced racial discrimination and were discouraged from voting through intimidation and fear, and Native Americans weren’t considered U.S. citizens until 1924. Women living in U.S. territories faced similar challenges; they were considered U.S. nationals, not citizens, and therefore didn’t share the same rights as those born in the continental U.S.

Despite the amendment’s passing and the decades-long contributions of Black women to achieve suffrage, a number of methods were used to keep segments of the population from voting. Most were targeted at Black Americans in the Jim Crow South, but Latinos, Native Americans, and Asian Americans also faced obstacles in the Southwest and the West. Literacy tests, invasive registration forms, interpretation tests, poll taxes, and outright violence were all used to keep people of color from voting. Literacy tests were administered and interpreted arbitrarily, and registrars could ask citizens test questions at their discretion. They had the authority to pass or fail applicants with no explanation. These didn’t end in some states until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which allowed for the registration and voting of historically oppressed minorities. Interpretation tests, involving transcribing or translating a passage of a complicated piece of writing, didn’t end until the late 1950s when courts struck them down for being too arbitrary. Other methods included poll taxes, which were particularly effective in the former Confederate South due to the poverty in the Black community. So, they couldn’t afford the tax, and invasive registration forms designed to intimidate, discourage and disqualify applicants.

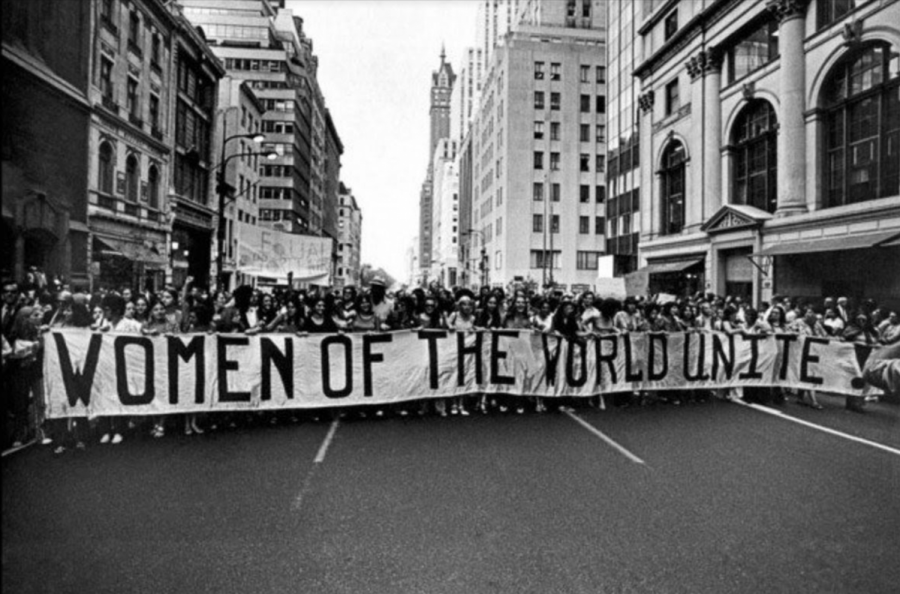

It took over 40 years for all women to achieve voting equality, but the United States has made tremendous progress in the fight for women’s rights. However, there is still work to be done. An increasing number of women are taking prominent roles in the battle for equality, such as Hillary Clinton, the first woman to receive a presidential nomination for a major political party, and Kamala Harris, the first woman and the first woman of color to serve as vice president of the United States. Women across the country and around the world are empowered to step up and fight for what’s right.