The Power Struggle of Literature

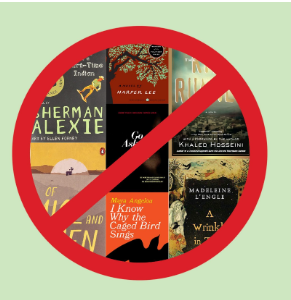

During the 2021-2022 school year, more than 1,600 books were banned from school libraries.

February 28th, 2022. Marched in those decked out in pride flags and masks, bearing rather emotional testimonies to Hunterdon Central’s Board of Education, crying out their opposition to the rumored ban of LGBTQ+ books. Within the walls of Central’s Little Theatre (and spilling into the Commons), a sea of rainbow unified those in support of inclusive curriculums, while those associated with Team PYC (Protect Your Children) came in opposing it. During the night, people ranging from young students to parents to HC faculty stood in front of the mic (many for the first time) for their allotted 3 minutes, making their case in support or opposition of the LGBTQ+ book ban/inclusive curriculum. After hours of cheering, booing, and tear-shedding, the historical night finally concluded.

January 24th, 2023. Almost a year before the first anniversary of that notorious BOE meeting, Washington Township High School (in Gloucester County, NJ) made the decision to ban Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye; a novel that follows an 11-year old African American girl, Pecola, post-Great Depression, who wishes to have “the bluest eyes”. It tells the story of the impacts of racism and colorism, but also includes depictions of her father sexually assaulting her, which raised the eyebrows of many parents, ultimately leading to the decision to ban it.

This movement to outlaw inclusive (and often explicit) literature/curriculums has made its waves across America. From Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, rejecting an AP African-American Studies pilot program, to banning the notorious critical race theory across several conservative states, social studies and English departments have been pushed to the headlines. This movement, in particular, focuses locally, with members bringing their concerns to local board meetings, community Facebook groups, etc, often claiming of “indoctrination” and “traumatization”. However, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, indoctrination is defined as “to imbue with a usually partisan or sectarian opinion, point of view, or principle.” Thus, providing an intersectional and inclusive range of views seems to be antithetical to partisanship. It’s important to note that this movement is purely responsive, meaning it is only the reaction to some other action (ie All Lives Matter is a responsive movement to Black Lives Matter). In this case, it’s responsive to widespread inclusivity.

At Hunterdon Central, the policy on controversial topics is as follows: “Free discussion of controversial issues –– political, economic, social––shall be encouraged in the classroom whenever appropriate for the level of the group…Pupils shall be taught to recognize each other’s right to form an opinion on controversial issues and shall be assured of their own right to do so without jeopardizing their relationship with the teacher or the school.” As heard at many board meetings, this encouragement has hit a sour note with some parents. Mrs. Bousum, a freshman English teacher, believes that this response is often a result of “feeling uncomfortable with topics of the life of the writer or main character, so they project that personal discomfort onto others.” Especially due to Central’s relatively progressive policies in an almost politically 50/50 area, these issues become even louder.

So what happens when these books get banned? According to an avid freshman reader, Ainsley Dahl, “The information might not be available to people which can lead to misunderstandings about things. Oftentimes, it’s also important to know, but because it’s a sensitive topic, they veer away from it, further perpetuating a ‘cycle of unknown.’’” This pro-longed taboo makes it increasingly difficult to then have discussions where disagreements exist. Thus, assumptions and dominant narratives become stronger.

Additionally, Ainsley feels “people think they’re being [protective] of teens, but it can be harmful because they’re not having that information/insight of things that happen. The issues that become banned are often the most important ones, and forbidding that withholds crucial understandings. Really, it’s only short-term protection because they’re going to face the issues later in life anyways.” Similarly, Mrs. Bousum agrees that students are more harmed than protected when books become banned. She says that by “reading these issues is by no means going to harm, but rather going to enlighten. It’s like saying you shouldn’t play video games because you’re going to become violent.” She also notes that banning books takes away readers’ autonomy over what they want to read, believing it shouldn’t be someone else’s

decision. Thus, the argument to withhold information, and therefore “innocence”, is faulty.

Ironically, the first anniversary of the BOE meeting comes just before Read Across America Week. Many will say it’s quite symbolic of the power literature holds and its struggle with those who fear it. In fact, because of that power, Mrs. Bousum encourages “whenever a book is banned, chances are, you should read it…It should raise curiosity. Find out ‘Why was it banned?’ ‘Why do people feel it was so dangerous?’” As we enter a rise of banned books in New Jersey, the power that knowledge holds becomes magnified, and taking hold of it becomes invaluable. Gasping that may just start with opening up a copy of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eyes.

Work Cited:

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/indoctrination

https://www.bestplaces.net/voting/county/new_jersey/hunterdon